Thank you, Jacob Christian Schäffer

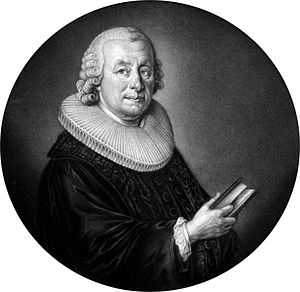

There are big names in every industry and aspect of culture. Isaac Newton, Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, Madam Curie, Steve Jobs. If you work in laundry, Jacob Christian Schäffer (1718-1790) should be on your radar and your thank-you list.

Like many inventors of his day, Schäffer dabbled in many areas of science. He was a German dean and professor, a theologian. He was also a botanist, mycologist, entomologist, and ornithologist. In other words, he studied plants, fungi, insects, and birds. He probably got pretty dirty in pursuit of his studies, and so his most famous invention was born: the first washing machine in 1767.

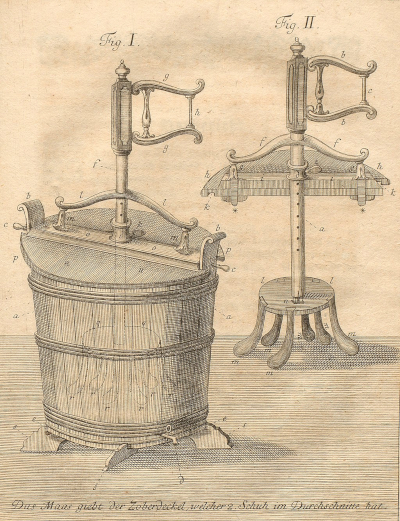

A thing of beauty

Schäffer’s washing machine included a wooden barrel-style tub with a mechanism that stirred the clothing at the bottom of the barrel and agitated the water. A lid kept the water from sloshing out, and a handle made the mechanism turn.

The principles Schäffer worked out form the basis of today’s high-tech industrial laundry machines (or even the ubiquitous home or laundromat machine). There’s a tub of some kind. The operator puts clothing into the machine with water. The clothing is agitated with whatever detergent is preferred. Our modern machines may have lights and computer panels, automated cycles, and robotic loading or unloading, but they are really scaled-up versions of the first concepts used in his machine.

Who is this guy?

Born in 1718 in Querfurt, Thuringia, Germany, Schäffer is hailed by many scientific disciplines as an early innovator.

- Optics. He designed a system of lenses and prisms that are still used today.

- Printing. He created paper manufacturing tools and suggested using plants such as poplar, moss, and hop that paper pulp manufacturers might not have used without his experimental work.

- Dentistry. He dispelled the idea that small worms cause toothache and decay when they get into the tooth and eat away at its structure. (Whew! I’m glad we cleared that up.)

- Medicine. He published a handbook on botany and the medicinal effects of plants for doctors and pharmacists.

- Fungus. He produced four richly illustrated volumes on the subject.

- Biology. He proposed a system of birds classification based on their legs’ structure.

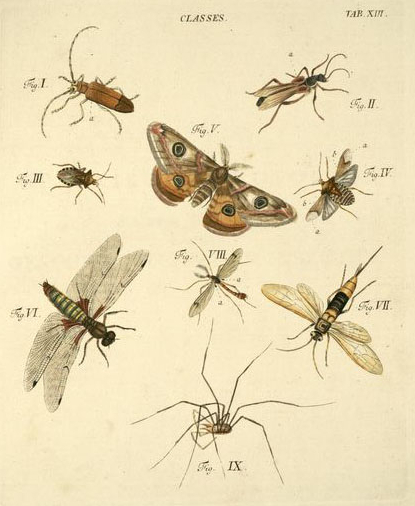

- Insects. He wrote a three-volume work that included 280 hand-coloured plates of copper engravings illustrating about 3,000 insects.

- Inventions. He also invented a type of saw and a furnace, among other practical things, but he is best known for his washing machine.

Why a washing machine?

With all the things going on in Schäffer’s mind, why would he turn his considerable intellect to basic clothing cleaning? The most likely answer is that something about the process made him angry enough that he wanted a solution. Until his machine, laundry was done strictly by hand—or even feet.

Launderers immersed clothing in water and then beat or stomped on it to try to drive the stains out. The early Romans had collection bins all around the city where people could deposit urine, which was then used to clean clothes. The ammonia it produced proved an effective stain remover, though the aroma was something else altogether. This practice continued into the Middle Ages with “chamber lye” used by launderers, named for the chamber pots from which urine was collected.

Soaps made from olive oil and lava ash also helped to remove stains, and the introduction of very hot water added another dimension to cleaning. But essentially, it was a hugely labour-intensive chore. No wonder people in the Middle Ages only cleaned their clothes about twice a year. (They bathed about once a month because they thought diseases like the plague spread by contact with water.)

It would be another 25 years after Schäffer created the washing machine before someone took the process further and made a drying machine. But that’s a story for another day….